At the bottom of Broad Street sits St John on the Wall. At one point or another, every Bristolian will have passed beneath the great stone archway, beneath the looming spire and past the doorway to the crypt - as they have for more than six centuries.

This is the last remnant of Bristol’s medieval city walls and the only one surviving out of nine gatehouses. St John’s was built literally into and on top of Bristol’s defences in the 14th Century, on the site of an earlier 12th Century church.

St John’s from Quay Street - the original height of the wall can be seen over the right archway

People leaving the safety of the city walls would stop in for a prayer before braving the perils of medieval travel. But, the congregation has dwindled so much that the church is now redundant and in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust (CCT).

Philippa Wood is the CCT’s local officer for the West region, covering 29 redundant churches.

She said: “With congregations now much smaller and with society as a whole less committed to donating to the church, this results in a considerable gap between income and necessary expenditure.”

The spire of St John’s underwent extensive repairs last year which cost almost £50,000. With the average income of the church being just over £7,000, St John’s faces a consistent shortfall in funding, which is “certainly the case across the wider region”.

Another issue is the threat of theft or vandalism. Lead from the roof was stolen in 2019, which can imperil the ancient interior. Significant late-medieval wall paintings have been lost at St John’s over the years. Some remain covered by a coat of white paint but it is currently beyond the coffers of the CCT to restore and preserve them.

The 15th Century crypt at St John’s is also in need of stabilisation work and has been flooded in the past.

Ms Wood went on: “It's important to remember that churches were not always pristine even in their heyday; at times the crypt at St John's has, I'm told, been used as a market place with animals brought into the space.

The crypt at St John’s has been flooded and damaged due to neglect in the past

“My role [at the CCT] is to help communities build their own vision and have the freedom to run their own events. I’m enabling communities to get creative and decide what they would be interested in doing that would support the church and raise funds to preserve it into the future.”

“These are spaces that have historically been the centre of their communities, one of the only spaces where people of all classes would come together on a regular basis. I feel this is a legacy that we can and must extend into the future.”

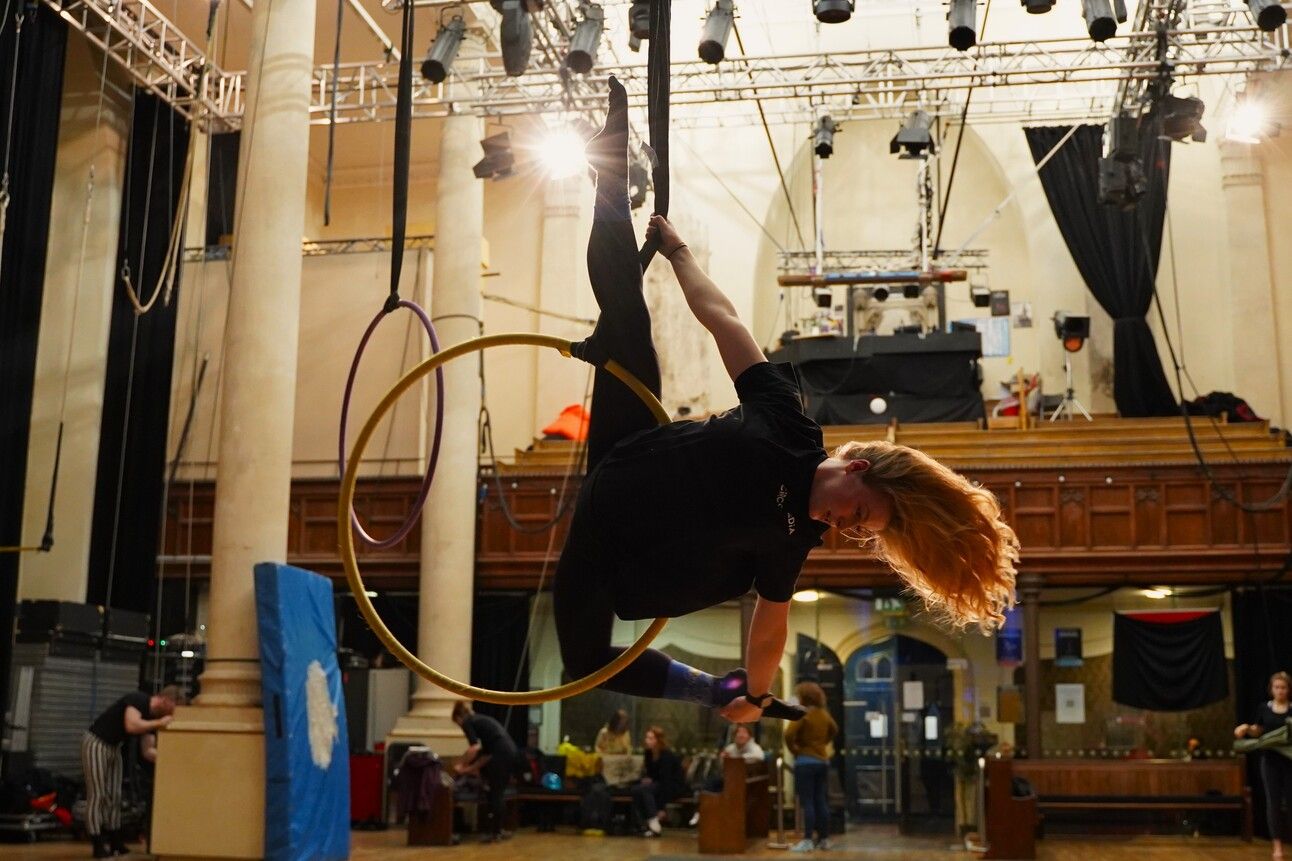

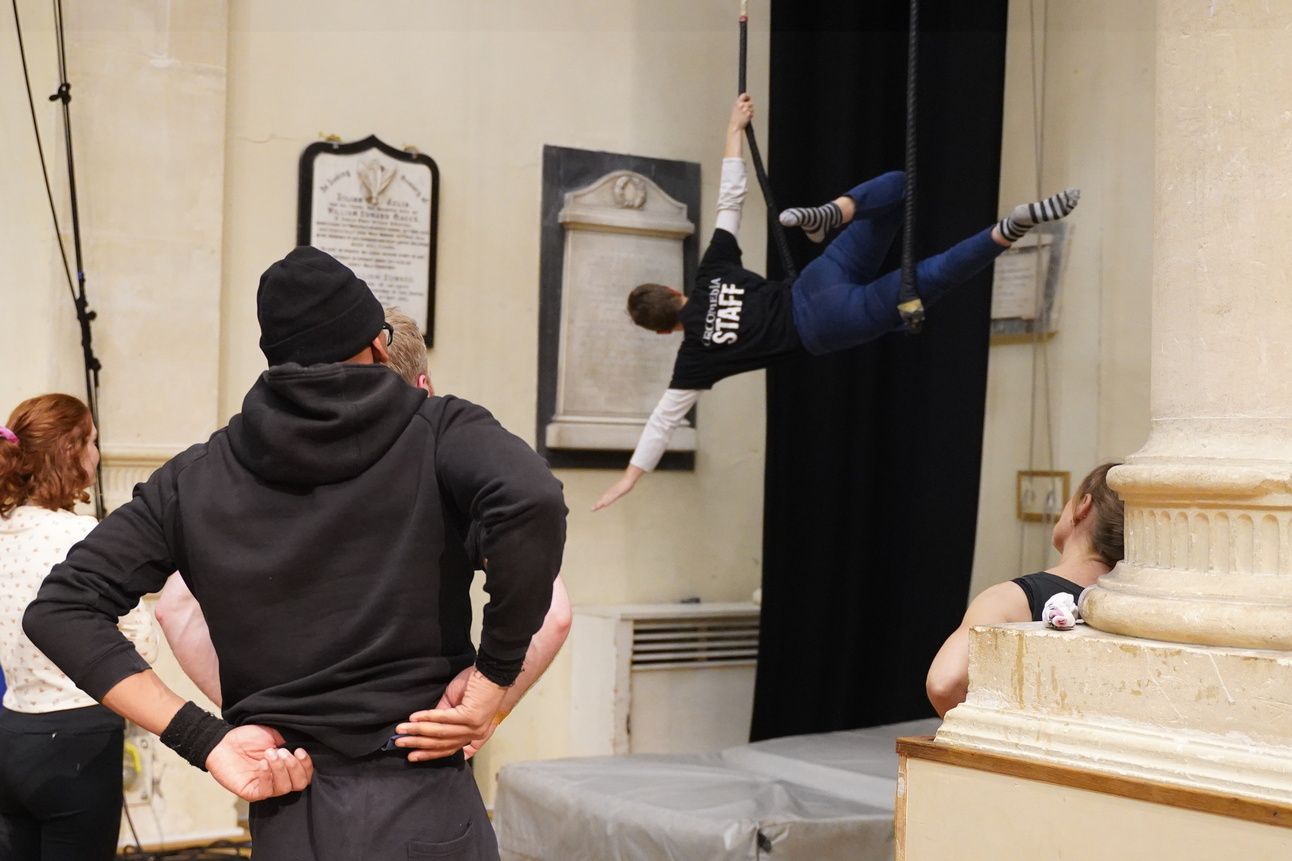

Circomedia

Elsewhere in the city sits the iconic church of St Paul’s, which gives its name to the wider district in Bristol. St Paul’s was built in the 1790s but closed in 1988.

The CCT took over the site in 2000, and the church has been leased to one of the UK’s largest circus schools for the last 20 years.

Zannah Chisholm is the CEO of Circomedia. She told HANA News: “The Bath Stone was really damaged by the time the CCT were looking at it. There was a lot of damp and crumbling of some of the stonework.

“It had been left uninhabited for quite some time, so there was a lot of work to do. But, the ceiling is still there, the stone windows are still there and under the spring floorboards, the original tiles are still there.

The church now functions as a circus school teaching kids, adult and degree-level classes

“There is a massive rig [on the ceiling], which enables us to hang hoops, trapeze, rope and lighting for the performances. We are the only place in the country that has a high-flying trapeze, and you can fly from one end of the nave into the chancel. It remains a really special place and has become really iconic for Bristol and for circus people.”

Circomedia teaches classes from age two and upwards. They offer a BTEC course in Circus Performance, as well as a BA and MA degrees. St Paul’s is host to a variety of performances each month, ranging from trapeze to magic and cabaret nights.

The school teaches acrobatics, trapeze and aerial performance

“There is something about the way churches have always been built,” Ms Chisholm continued, “which is about people coming together. That works just as well for an audience coming to watch a performance as it does for a congregation to come and worship.”

Zannah Chisholm, CEO of Circomedia said: “When we first took over at St Paul’s, we had people with a vision. For us, it works perfectly because we need the height, the depth and the width.”

Trinity Centre

Holy Trinity Church in East Bristol was completed in 1832, to serve the expanding community of St Phillips in the midst of the Industrial Revolution. By the 1960s the congregation of this 1,500 capacity church had dwindled to a dozen regular attendees.

The Diocese of Bristol took the decision to close the Church in the 1970s. Following numerous refurbishments and incarnations, the church has been under the tenure of the Trinity Community Arts charity since 2003.

Bristol Northern Soul Club is just one of many events at the venue

Dr Edson Burton is Curator at Trinity. He told HANA News: “Trinity had fallen into extensive disrepair, its bright Bath Stone was discoloured, some of its windows were cracked and the false floor was deemed structurally unsound.”

The repurposed church has long been touted as a pillar of the Easton community and an iconic Bristol arts space. Over the years, it has been host to such big names as Jah Shaka, Portishead, U2, Joy Division and New Order. The Trinity Centre also hosts community markets, dance nights, art shows and talks.

Young and old combined, enjoying Trinity’s dancefloor

Dr Burton went on: “Buildings like Trinity are the most visible non-commercial spaces in residential areas. In a diverse society they offer the opportunity for various communities to come together singularly and through interaction.”

Dr Burton added that there are fewer and fewer buildings for meaningful interactions within the community in modern Britain.

St Thomas the Martyr

Across Bristol Bridge and down an inner city alleyway, you will find St Thomas’. This grand Georgian building was built in 1789 on the site of a 15th Century church, and sits opposite another iconic music venue, The Fleece. Little now survives of the old parish buildings, once occupied by glovers, glassmakers and wine importers whose businesses supported the church.

One of the few remaining inns in the parish is the Seven Stars Tavern, right next to St Thomas'. Here, Reverend Thomas Clarkson gathered information on the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and his evidence helped bring about the abolition of the Slave Trade in Britain.

Bristolians enjoy a unique night out at St Thomas the Martyr

Now, St Thomas’ has been deconsecrated and is rarely open to the public. Whilst the church is in good condition, any sudden restoration or maintenance works could run into the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands.

On one late autumn night, The Fleece took over the church and created a stage and dancefloor in the chancel. The 18th Century organ, which supposedly gained the admiration of Handel himself, now looms over revellers grooving to electronic beats.

The Georgian columns amidst the mist and partying Bristolian

What is a unique, grand and airy space to have a party did - for the night - find a new use, and brought in a wealth of funding to preserve the building.

HANA News spoke to party-goers Sam and Valerie at the church. Sam said: “I think making use of this beautiful building is paying our respects. Letting the church sit empty or derelict is what is disrespectful - to the people who built it and used it.”

Valerie and Sam outside St Thomas’

Valerie said: “I would hate for it to be left in ruin or taken down. I would absolutely hate to see such architecture be lost, whether it’s within religion or not.

“Use it for whatever is needed to keep it. The benefits to fill a new housing quota, for example, is nothing compared to losing hundreds of years of history with the strike of a hammer or bulldozer.”

‘At risk’

Nearly 1,000 churches and cathedrals around the country are at risk’ of falling into disrepair or being demolished.

In Devon, the 12th Century St Petroc’s is crumbling and closed. Church authorities said work to make it watertight could cost £400,000. In Suffolk, St Andrew’s church at Walpole was left without flooring for two decades. The examples are endless, up and down the country.

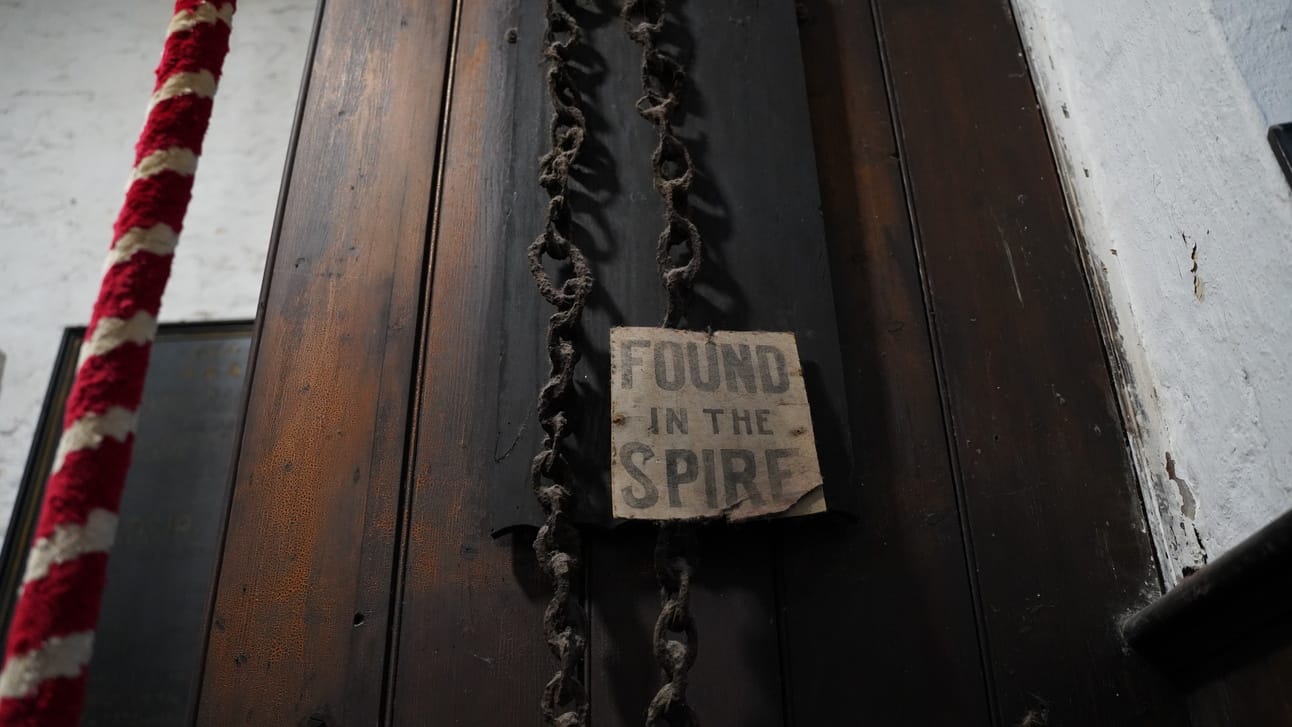

Medieval chain link on display in the belfry of St John’s

If the walls of St John’s - and countless other churches - could speak for themselves, they could tell you about the reigns of 35 monarchs, 58 prime ministers, several civil wars and at least four major plagues in Bristol. The walls could tell you about the discovery of America and how the port city of Bristol flourished.

The walls could tell you about the two sieges of Bristol in 1643 and 1645, during the English Civil War. They could tell you about cannon fire raining down on the city from Brandon Hill and St Michael’s Hill. They could tell you how Englishmen slaughtered each other in these very streets, battling down Christmas Steps up to only feet away from the gatehouse.

The walls could also tell you about Nazi bombs and how they wiped out an entire district, now known as Castle Park. They could tell you about the slow birth of democracy in this country, and the bitter, violent defence of it.

Reinstated medieval stained glass

If the walls could speak, they could tell you about generations of religious violence and revolution. They may tell you how someone saved the medieval stained glass windows from the Puritanical hands of vandals, and put them back in piecemeal.

The walls would tell you how people have - for generations - feared, prayed, loved, married, died and paid their respects within that church. If the walls of St John’s could speak, they would tell you about this country - who we were, and who we are now.

But they can’t. It’s up to us to tell their story.